There are few experiences more humbling than the weight of history when one finds oneself standing in its prodigious shadow. Most historical landmarks are noted for one important event or an association with a person of significance, which can be humbling enough. Rarely does an edifice find itself the focal point of history several times over, much less for the entire length of its service to the community. The home at 3120 Good Shepherd Road is just such a crossroads of history; a confluence both humbling and enlightening.

Since 1969, the two-story home, with its attached chapel, outbuildings and vast park-like grounds has been the home to the Emerick family, residential and commercial real estate developers for over five decades. It’s here that Lewis and Sara Emerick raised their children and conducted the highly successful family business, via offices located in the back of the house. Much of the Mesilla Valley as we know it today was conceived and brought to life through those very offices.

But the history conducted during those years does nothing to diminish the achievements of the property’s first half century.

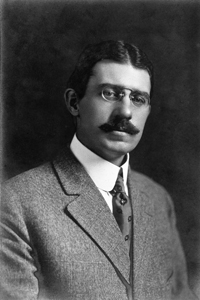

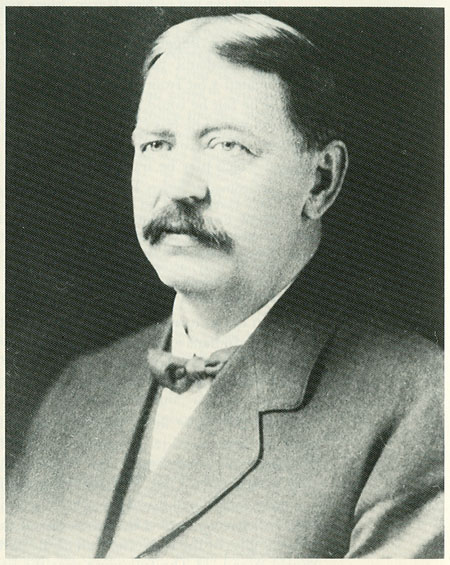

Originally 13.7 acres of land, purchased in April 1909 by Dr. Winifred E. Garrison, president of the New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts – what is now New Mexico State University – the property became the site of a large southwestern-style hacienda, with high ceilings, sixteen-inch adobe walls and a series of rooms surrounding a two-story inner courtyard. Contracted to build the home, and adding to its initial significance, was premiere architectural firm Trost & Trost – a fact which has only recently come to light through the diligence of architectural champions, Mesilla Valley Preservation.

On April 5, 2014, MVP officially announced the addition of the Good Shepherd House to the Trost & Trost archive of homes which have survived in the Mesilla Valley after MVP President Eric Liefeld pieced together the historical puzzle that had eluded many for decades.

“There was some good research done back in the 80s related to Trost, but they drew some wrong conclusions,” he said. “We’ve got that all sorted out. There was a case of mistaken identity. The researcher assumed that the president’s house was on campus, but that was not the case. The president’s house on campus was built in 1918, but we had in our possession letters dated 1908 referring to Garrison’s residence from Trost. We had figured out a Mesilla Park connection, but didn’t think we would ever figure out which house it was. It was only after we figured out Garrison’s house was the convent that it all clicked together. It doesn’t make much sense in Mesilla Park, but it’s definitely in line with the Spanish revivalist style Trost was working in. It’s exciting because it’s a Trost style executed in adobe.”

During those early years, the hacienda served as a social hub for college functions and matters of state. Garrison, in addition to his duties at the agricultural college, was also a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, which ushered New Mexico into statehood in 1912. By the time Garrison stepped down as president of the college in 1913 and moved his family to California, the house had earned its reputation as a landmark of historical importance.

For several years the home exchanged hands, going through a series of ownerships until May 1928 when it began the next chapter in its notable march through history via its sale to Mother Mary of Saint Francis de Sales, Superior of the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity of the Good Shepherd. Victims of the Mexican Revolution of 1911, the order eventually lost its properties in Mexico and had to be evacuated to the United States in 1927. After a short stay in El Paso, the sisters discovered the property in Mesilla Park and began their tenure as its residents for the next four decades.

Though frequently beset by economic woes, the Good Shepherd sisters took on the formidable task of creating a convent and orphanage, making adobe bricks by hand and erecting several new buildings on the property, for use as dormitories, classrooms and other utilitarian purposes.

In addition to all this hard work, the sisters found time to raise money to support themselves by sewing and embroidering handkerchiefs at ten cents a dozen. Their beautiful needlework was consigned through an agent in New York City and much of it can now be seen in museums throughout the United States. A laundry room was also installed, where the sisters laundered everything from heavy drapes to delicate lace tablecloths for the good citizens of Mesilla, Las Cruces and El Paso.

By the mid-1950s, the Good Shepherd complex was the home to 115 girls between the age of 15 to 20, as well as over 100 orphans and young children. A cinder block chapel had been built adjacent to the original hacienda, using War Claims money received by Mother Superior Mary Vitalis Winkler, who had been interned in a concentration camp on the Philippine Islands during World War II, before taking over at Good Shepherd.

By 1960, however, the sisters had finally succumbed to their financial problems and began disbanding. Many of the girls were moved to foster homes, other schools or went on to begin studies at the University. In September of that year, one last attempt was made to keep the property running with the opening of Madonna High School. Seven years later, despite patronage from families throughout the region and parts of Mexico, the school closed its doors for good.

With the closing of the Madonna High School and the final departure of the Good Shepherd Order in 1967, the home fell into disrepair. But that was not to be the end of the story. A young couple living in a rental property not far away, on Bowman Street, saw potential in the grand old structure and in April 1969 Lewis and Sara Emerick purchased it from the sisters, thus beginning the latest chapter in the history of the home.

For several years after the purchase, the Emericks conducted a careful restoration of the old hacienda, though many of the outlying buildings had fallen so far into disrepair they had to be torn down.

The original woodwork and flooring of the main house were preserved and – with the exception of the replacement of the tile and the addition of skylights to the beamed roof – the inner courtyard also remains intact. A stone fountain and hanging plants give the enclosed space a serene focal point from which all else within the house branches outward.

Surrounding the courtyard at ground level are formal rooms of the hacienda. A living room, crammed to the rafters with antiques and personal reminders of lives well lived, occupies the front of the house, with music room at one end and library at the other. Three bedrooms and two bathrooms occupy either side of the house and a formal dining room and kitchen take up the back.

A staircase, installed by the Emericks when the original staircase in the courtyard had to be torn down, ascends to the second story from the dining room. Here, the original beamed ceilings are still intact and a large bedroom overlooks the courtyard, occupied by an antique bedroom set, rumored to have come out of the Amador Hotel and, before that, to have been connected to Maximillian von Hapsburg before his execution in 1867. All old houses have their ghosts, but a former Emperor of Mexico? You won’t find that just anywhere.

From there, the bedroom opens up into the large informal quarters, or what might once have been an open air sleeping porch and space for informal family gatherings. The windows to the outside have long since been glassed in, but those overlooking the courtyard are still open. This “room,” now filled with toys, books and other incidentals left behind by decades of children, grandchildren and great grandchildren, wraps around the courtyard, coming back around to the stairwell at an area where a third bathroom is located.

Because the property was to be used as offices for Emerick Real Estate and Construction, an addition was built to the back of the house, behind the dining room and kitchen. Easily closed off from the rest of the house, the office suites are accessed via the driveway that enters the right side of the property and extends, past a small mother-in-law casita, to the back of the property. Beyond the casita can be seen another historic building, originally built by the sisters to serve as a convent and now used as condominiums operated by the Mesilla Park Heritage Association.

On the left side of the house, attached by a walkway and a small grassed courtyard behind the offices, is the chapel, a large open room with high ceilings and beautiful stained glass windows. Because of a covenant with the neighbors, signed by the Emericks, the property cannot be used commercially, so the chapel remains private to this day.

Another large adobe structure sits in the far back corner of the property, where Sara Emerick houses her private museum. Sitting near the door is a vintage washing machine which, from the looks of it, was left behind by the sisters; basically a wooden barrel turned on its side, with a metal door across the top. History invades every nook and cranny of the museum, with its collection of antique silverware, furnishings, framed photographs and agricultural implements. Still, it is only a fraction of the history to be found on the property at the end of Good Shepherd Road.

“We have history here that goes to the heart of the community,” said Mary Mulvihill, an associate broker for Steinborn & Associates Real Estate and an amateur historian. “This is the history of the Mesilla Valley, right here, and when people ask me if the lights work, or if the fixtures are original, I just have to wonder. These are not the kinds of questions one asks about a piece of history. What we’re looking at is the bones of a one hundred and five year old historic home. Considering it’s adobe, this house is in great shape. They did a marvelous job building this home.”

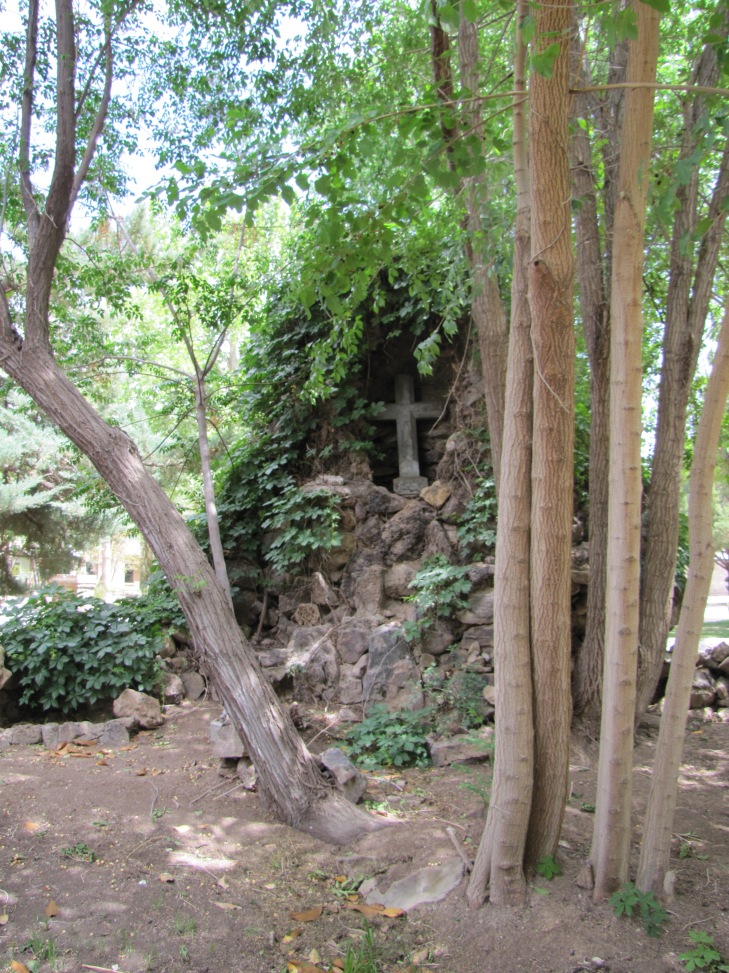

Gleeful birdsong and the wind blowing through the trees provide a serene backdrop to the park-like two-acre grounds of this historic property. Heritage roses release their heady perfume into the air. It’s very easy to imagine the sisters finding peace here, particularly in the grotto, originally constructed by them for that purpose and still standing on the outer edge of the grounds as a reminder.

History, it seems, has come to roost in the Mesilla Valley. With the impending sale of the property once again, this time by the 96-year-old Sara Emerick, one has to wonder what the next century will bring. What moments of significance will occur here in the quiet crossroads of history nestled away in Mesilla Park?

For all we know, the next chapter may already be underway.

A much shorter version of this story was originally published in the May 9 issue of the Las Cruces Bulletin. All rights reserved.

I find it extremely interesting . I was one of the children attending school in 1953 _1956

That’s awesome, Virginia! I’ll bet you’ve got some very interesting memories from that place. Such a feeling of history within those storied walls. I’m glad you liked the article.

Hello

I also attended this school around the same time as well

Hi Yolanda, I visited my aunt in 1946 with my Mom. I was 10, and they asked me to be in a procession on Corpus Christi Day. Elena

My sisters and were placed in the orphanage around 1950. I don’t

know how long we were there.

I would love to tour the property.

I visited my aunt, who was a nun, around 1946. I have a few of the relics they used to make, and I remember her working in the gardens, plus a lot of fresh fruit trees, I was 10 years old. The chapel was spotless. Elena Zuniga

I attended Madonna High School from Fall 1965 through Spring 1968. The school closed in Spring 1968 at the end of my junior year. (Your article says the sisters left in 1967. They left in 1968 at the end of the 1967-1968 school year.)

This house was the home of my grandfather, George E Ladd, when he was president of the New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts from 1913 to 1917. My mother spent many happy years here.